Fellig. Arthur “Weegie” Fellig. He’s the guy who responded with that simple “f/8 and be there” statement when asked how he consistently came up with those outstanding photographs that he made. And in making that statement he alluded to what was a philosophy of sorts that hinted at how to go about making great images…

A philosophy that in my humble opinion is understood by few people, totally misunderstood by most. And I must hasten to add that this-here post is going to be frowned upon by many a “photographer”, but then I’ve never been known for pulling my punches. So here I go again, upsetting a couple of hundred souls as I’ve done before…

To understand what Arthur Fellig meant, a bit of background is called for. Arthur Fellig was a photographer and photojournalist, known for his stark black and white street photography. Working in Manhattan, New York City’s Lower East Side as a press photographer during the 1930s and ’40s, and he developed his signature style by following the city’s emergency services and documenting their activity. Much of his work depicted unflinchingly realistic scenes of urban life, crime, injury and death.

Now, think about those terms above. Specifically “unflinchingly realistic scenes of urban life, crime, injury and death”, “photojournalist”, “city’s emergency services and documenting their activity” for a while, and three very obvious things should come to mind:

- Arthur Fellig had an uncanny instinct – a flair of sorts – of being exactly where the “action” so as to put it was playing out

- His compositions (the co-relationships) – between so-called subject, supporting subjects and context were highly effective in making an image. An image that…

- … literally transported viewers of the image to the location, made viewers see the scene as it was through Arthur Fellig’s eyes. And most important , actually feel what it must have been like to be there.

When asked how he managed to do so – and so very consistently at that – Felig simply responded with “f/8 and be there”. And therein lies the tale.

Let's start with the f/8 thingie, shall we?

I’m going to get just a wee bit technical here, but ever so slightly. So if you feel you’re technically challenged (no such thing IMHO, it’s just that you haven’t met an instructor who could simplify it enough. Till now, at least!), rest easy! You won’t even feel a hiccup!

All cameras have an opening in their lens through which light is admitted, light that then goes on to strike either film or a digital sensor. This opening in the lens is called the aperture. With me so far? What a foolish question, of course you are!

It follows that any opening must have a size. In the context of the opening in the lens (the aperture), that size is represented by a value that we’ll call Aperture Value (extremely imaginative, ain’t it?). And just like millimeters are represented as mm, centimeters as cm, meters as M etc., Aperture Value is represented as f-value, or more commonly f/value. And I’m not going to ask if you’re with me so far, because I already know the answer.

Trust me, it ain’t important to understand just why it is so, but f/values have the following typical… well, values:

f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22, f/32, f/44

Now, repeat after me: “I am not going to get scared by what Neville has to say, he will make it clear as clear can be!”. Good, read on…

The f/value determines what is called the Depth of Field or DOF. And before you go “Help, what’s this DOF thingie!!!!”, let me state that it’s really very simple.

Think of some of the photographs you’ve seen. In some of them, everything from foreground to background is clear, in sharp focus. And in some of them, only some things are in sharp focus, other objects in the background and / or foreground being rendered as soft, dreamy and out-of-focus. So what’s that got to do with that DOF thingie, and what’s it got to do with f/value?

When your camera lens focuses on any damn thing, it will be in sharp focus. In addition, there will be area in front of what you focused on, and behind it that will also be in sharp focus. That, in simple terms is DOF or Depth Of Field – the area in front of – and behind the subject focused on – that will also be in sharp focus.

Essentially, images with everything from foreground to background (typically landscapes) have a large DOF, while most portraits where the subject is in sharp focus and the background is blurred have a small or narrow DOF.

OK, so you’re nodding your head in understanding, but are still wondering what that’s got to do with our f/value.

Here’s how it goes: The smaller the value part of the f/value, the smaller (narrower) the DOF. And, the larger the value part of the f/value, the greater (larger the DOF). Or to put it simply – all other things being equal, a photograph taken at f/16 will have a large DOF, while a photograph taken at say f/5.6 will have a much shallower DOF. The three photographs below illustrate this; from left to right they portray images with a shallow Depth of Field (thanks to a small f/value), a medium Depth of Field (courtesy a medium f/value) and a large Depth of Field (owing to a large f/value).

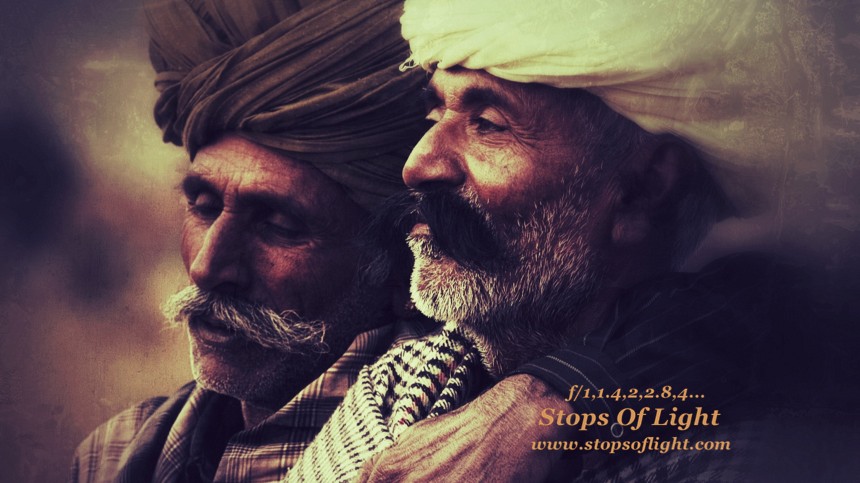

Clicked on the Pushkar Camel Fair leg of my annual Five Stops of Light India Photography Tour, the photograph above is a classic example of the the use of a shallow Depth of Field. Seeing as I did the very real sense of closeness between these two friends, my objective was simple: To highlight the joy of the meeting between two friends after a long gap of time. I cropped closely to eliminate everything that would take away from this sense of intimacy. It was also important that nothing in the background take away from what I wanted to portray. The solution was simple: A small f/value(f/4 or f/5.6) resulting in a narrow depth of field.

Fellig's f/8 fetish

When asked how he managed to get the images he did, Fellig would just go. One But why f/8? The answer is to be found in the very nature of his work – work that involved photographing urban life, streets, photojournalism…

Now think about all these genres and you’ll realize that there are times when – depending on what would have been unfolding in front of his eyes – Fellig would have needed to either (a) render everything from foreground to background in sharp focus, (b) have the focus drop off in a nice gradual fashion, or (c) only have the main subject in sharp focus and throw everything else dramatically out of focus. And of course, as we saw above, he’d have to essentially achieve either of these results by changing his f-value. Seems simple, till you think about just how rapidly real-life events play out out in the context of urban life, street photography and photojournalism…

There’s no scope for error. No question of posing of subjects. All you get is an fraction of a second to decide on what f-value to use, and set it!

Let’s try and visualize this, shall we? There’s Fellig out there in the street and he sees this thing unfolding in front of him that tells the story. And he needs to photograph it with a shallow Depth Of Field with an f/value of f/5.6 or lower. Except that the f/value on his camera is set to f/16. So there goes Fellig turning that dial that changes the f/value, and several turns at that to get to f/5.6. Except that by the time he gets there.. “Oops! Sorry Mr. Newspaper Editor, but I couldn’t get the shot. My camera wasn’t at the settings called for, and by the time I got around to setting them the moment had passed…”

Or, how about this:

There’s Fellig out there in that street again and he sees this thing unfolding in front of him that tells the story. And this time he needs to photograph it with a large Depth Of Field with an f/value of f/16 or higher. Except that the f/value on his camera is set to f/4. So there goes Fellig again, turning that dial that changes the f/value, and several turns at that to get to f/16 . Except that by the time he gets there.. “Oops! Sorry again Mr. Newspaper Editor, but I couldn’t get the shot this time across too. My camera wasn’t at the settings called for, and by the time I got around to setting them the moment had passed…”

Of course one can’t be certain, but I have a lurking feeling that Mr. Newspaper Editor’s reaction wouldn’t be much different than that of J. Jonah Jameson – the editor of the The Daily Bugle newspaper where Spiderman held his day-job!

And that’s where Felling’s f/8 fetish stems from. Let’s look at it in greater detail, starting with that list of f/values I listed out towards the top of this post.

f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22, f/32, f/44

And viola! What do we see? That f/8 is right there in the middle. It’s middle-ground, offering a compromise between a shallow depth of field and a large one.

Essentially, if Fellig set by default a f/value of f/8 before he went prowling those streets, he would be in a position to make a shot which struck a fine balance between everything being in sharp focus on the one hand, and contextual elements being slightly out of focus. If there was no time – not even a split second – to change his f/value, he’d just take the shot. And the chances would be that the shot would achieve its objectives of showing what he wanted to show. Yet, that’s just part of it…

The other part to the f/8 bit is that being in the middle, it’s not too far from either end. Essentially, if Fellig had a moment or two to change his settings based on whether he wanted a shallower or larger depth of field, being at f/8 ensured he could get to his desired f/value faster, with far fewer turns of the dial.

And that’s that about the f/8 thingie in Fellig’s equation; why he chose to keep his camera by default on that aperture value. I’d encourage you to do so too. Time we moved on to the second part of the equation I think.

"and Be There"

“Be There”. That – according to me – is the most misunderstood part of Fellig’s equation on how to go about making great photographs. The misunderstanding stems on account of two things: (a) paying too much attention to the f/8 bit in Fellig’s formula(essentially, the technical issues of photography, thinking it’s all about the camera), and (b) thinking that “being there” is about being at a place in the physical sense.

“Wait a minute,” did I hear you go? “What the hell else would it be? Of course you need to be there to make an image of whatever is unfolding! How else would you get the shot?!?!?!”

That’s what went through your mind, didn’t it? Thanks for admitting it! And therein lies the problem.

The mistake that many a photographer makes – as did I – is about paying attention to the “There” in “Be There”. In the process, they ignore the importance of both the word “Be” in itself, as well as that of what’s really implied in the sum total of the words “Be There”. And since a picture is worth a thousand words, I think an image or two would best illustrate this…

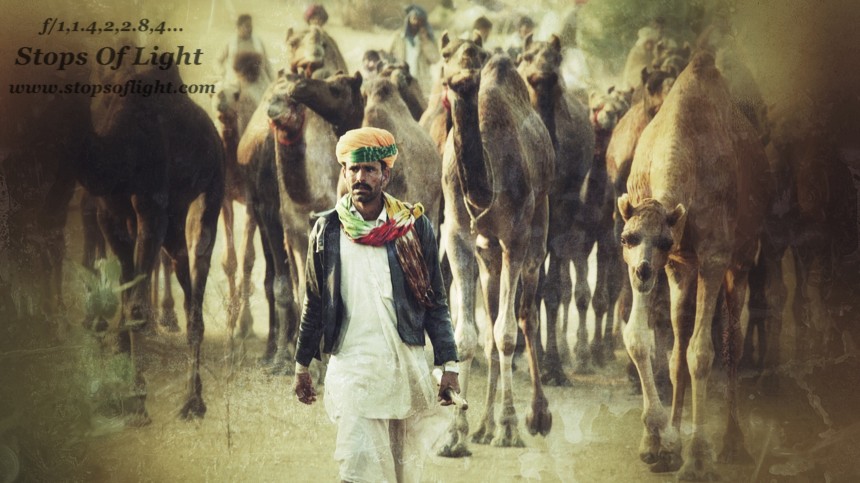

Even a cursory examination of the above two photographs makes one thing obvious: Impeccable Timing. Not just in capturing the action, but capturing it in a fashion, and that very moment when – as Henri Cartier-Bresson described it – “… the elements are in perfect balance”. And that’s the ideal photograph for you – when all the disparate elements come together just perfectly in a cohesive whole. Without it, there’s an imbalance. Without it, there’s chaos. Without the elements being in perfect harmony and working together, the eye is lost – and a picture is broken.

The trick hence lies in seeing the confluence – the coming together – of elements to form a cohesive whole. Coming together – again to quote Cartier -Bresson – “for maximum emotional impact“. Seeing it before it happens, anticipating it, visualizing it. And then taking the shot when it does happen…This is Being There.

Being There is not being there physically. Think about just how many “photographers” go to Varanasi. Or Ladakh. Or anywhere. They’re all there physically. But how many come back with really evocative photographs? Evocative original photographs, and not mere copies of the compositions of others? Few and far between, I’d think.

The reason is this: it’s not about the f/8, f/anything, ISO-anything or Shutter-speed-anything. It’s not about the “being There” either. What it is about really is Being Wherever You Are!

What do I mean by “Being”? It’s a heightened state of awareness. Of the world around you, its building blocks, and how they are connected both to each other and to you. That, is Being. And when you can just Be, you can be that state – for that is exactly what it is, a state – anywhere! You are – literally with eyes, mind, heart and soul – wherever you are! That’s why I say my gear consists of “eyes that see, a mind that thinks and a heart that feels” – that’s Being.

And that’s the single most misunderstood part about Fellig’s “f/8 and Be There” formula. It’s about Being. It’s more about You than it is about Place. ‘Nuff said!

Ooops… almost forgot about the bit where it’s time about the shameless plug. Scroll below, willya?

from snapshots to great shots

the art of seeing

Photography Workshop

“Because Photography is just this: Being!”