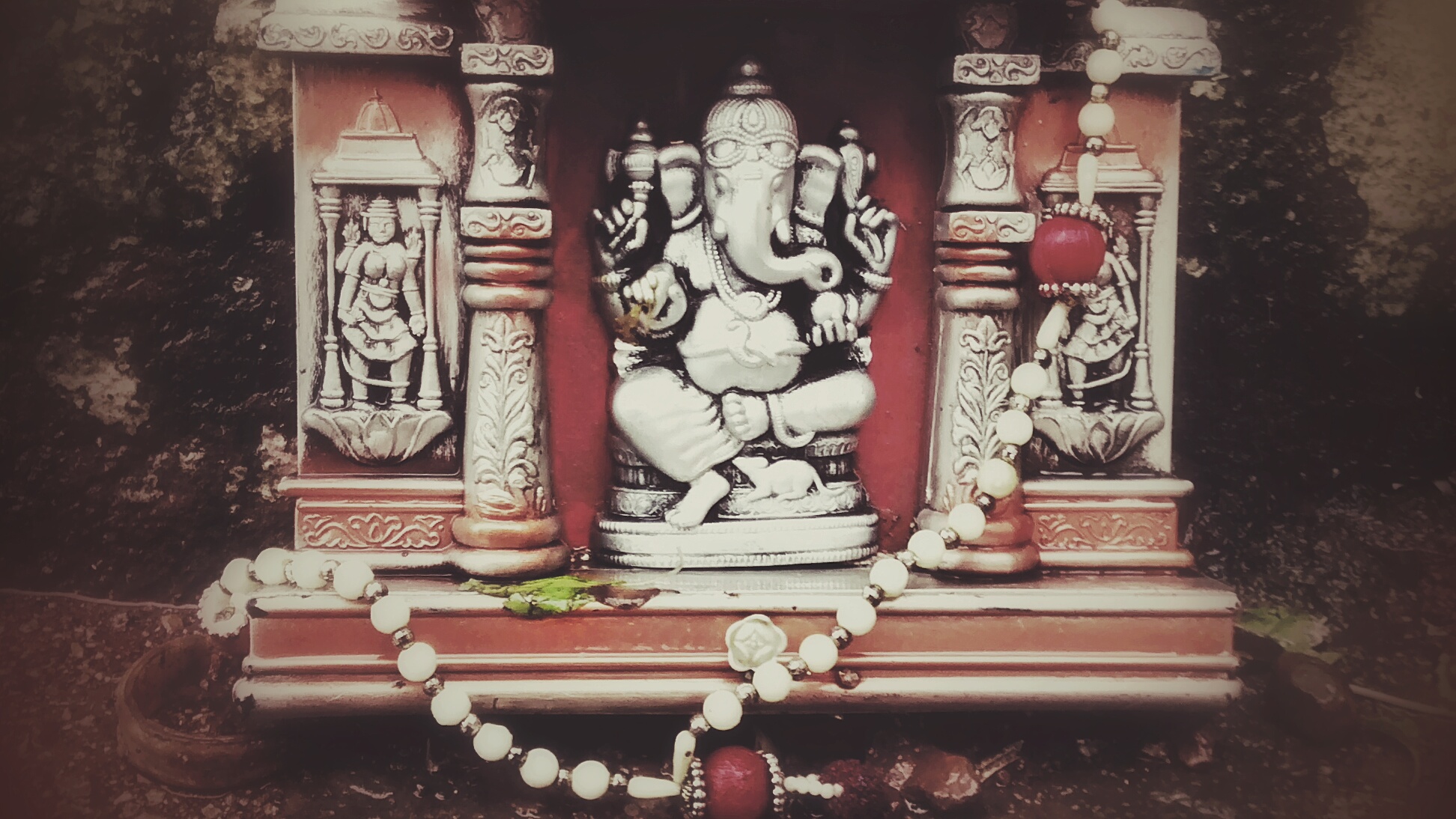

She raised an eyebrow. “This photograph? You want to use this to illustrate what you wish to put across?? I’m not too sure it’d cut the grade. Even you’ve got to agree it definitely doesn’t rank amongst the best of your images, given its lack of clarity and sharpness. And some highlights are obviously blown out. I can understand it’s a cell phone shot, but couldn’t you use a better picture to talk about what you want to?”

I could understand where she was coming from, the photograph – the one that graces the top of this page – having been taken with a humble MotoG, in 16:9 aspect ratio at that (which essentially meant the camera had a maximum resolution of 3.4 Megapixels), and on a dull overcast day to boot. Neither the best of cameras nor the best of days to be making images. Especially when it came to making an image of what I chose to illustrate what is the topic of this post. But then, there’s more to photography than the camera, and – if I may be given the liberty of punning – there’s more to photography than meets the eye.

“Drishti, that’s one of the reasons I’ve chosen to use this image,” I said. “The fact that it is not a technically perfect image. The imperfections. And of course, because it symbolically and literally communicates the message I wish to put across.”

“Which is what??” she asked. “I’m sorry, but this photograph is surely not the best of images when it comes to the topic you plan to write about – Darshan.”

“Be patient, kid. I’ll get to that,” I said. “But first, I have a question for you: what appeals to you more – a technically perfect photograph taken by a ‘photographer’ who’s mastered exposure but didn’t know why they were taking an image? Or, a technically imperfect sketch made by a child depicting a family outing?”

“The one made by a child, of course,” she replied. “But that’s not you, you aren’t a child drawing imperfect lines, and you aren’t a photographer who doesn’t know why they’re taking a photo. You’re capable of….”

“Hold it there,” I said. “The issue here isn’t what I am or am not. The issue here is why a drawing – with all its imperfections – made by a child is more appealing to you than a technically perfect photograph taken by a photographer who doesn’t know why he or she is taking a photograph. Care to think about this?”

She narrowed her eyes for a moment, I could see her mental gears turning. “Because that child felt something when it made that drawing?”

“Bingo,” I went. “Because that child was there in that picture! Not in there necessarily as a subject – the child could have drawn just its parents – but in there emotionally, in the act of making that drawing.”

“Ansel Adams!” she exclaimed. “Was that what he meant when he said…”

“That is exactly what Adams meant,” I said. “When Ansel Adams stated that ‘There are always at least two people in a picture – the photographer and the viewer’, amongst the many things he was alluding to, was that it is imperative for the photographer to feel something before taking a shot. That is ‘putting oneself in the picture’, that’s why we usually end up liking a child’s drawing more than a thoughtless photograph. If the photographer doesn’t feel anything, the chances are that the viewer won’t either. Because the photographer wasn’t ‘in it’.”

“I get it!” Drishti exclaimed loudly. “But I still can’t see what it has to do with the topic at hand – Darshan!”

“Patience, young grasshopper,” went I, making like Master Po. “I’ll come to that in just a moment. But first, tell me this: those terms we used – ‘being in there’, ‘feeling something’ etc., – could you come up with a word or two that sums that process up?”

It took her a minute for her to revert, but when she did, the words brought a smile to my face.

“Involvement”. “Participation”. “In touch with”.

“I couldn’t have put it better, Drishti! Those were exactly the words I wanted to hear! The child’s work appeals to us because we somehow feel – through her oh-so-childish drawing – her level of involvement, and her degree of participation in what was happening there. We sense the very real connection between what she feels inside her to what was happening on that outing. We sense her efforts – efforts that come out so beautifully – in expressing her impressions of that outing. And that is Art – Expressions of Impressions. And it’s only possible when what’s inside is in touch with what’s outside. And the child can do it flawlessly because what matters to her are just she and her impressions. And our ‘photographer’ fails because he has totally neglected what matters, concentrating instead on the camera.”

She looked at me in wide-eyed amazement. “That’s just so true! I never thought of it that way.”

“Wait,” I said, leaning towards her. “We’re not through yet. We’ve still got to deal with ‘Darshan’, remember? What does that term mean?”

“Well, you know what it is – that thing we Indians do in temples,” she said carefully, wondering if it was April 1st. Or so I figured based on her wary expression.

“Terms! Define your Terms,” I said, the pit bull in me coming to the fore. “You know what a stickler I am for clear and concise definition of terms, girl! Or, at the least, tell me what it is we do in temples that constitutes Darshan.”

I could tell she knew I was getting to something, the way she paused before speaking, choosing her words with care. “I’d say Darshan constitutes us looking at the presiding deity in the temple,” she ventured.

I knew that one was coming. I just simply knew it. And I had my response ready. “Looking at? Or, gazing at?”

“Eh? Aren’t they the same thing?”

“Well, not really,” I replied. “Looking at something is you know… well, you look at it for a moment and move on. Gazing on the other hand has connotations of lingering for a period of time. And while this may seem elementary and unconnected to our discussion, bear with me for a few more moments. I’ll show you just how deep this rabbit-hole goes!”

“O.K., so tell me,” I continued. “Going to a temple, standing before the idol of a deity and looking – or gazing – at it because either (a) one has been forced to do so by one’s elders, (b) everybody else is doing it, (c) it would be impolite or disrespectful to not do so, or, (d) it’s the done thing… Do any of these things constitute Darshan?”

“Of course not,” she shot back. “That’s mere mechanical form! There’s no reverence behind it, no devotion, there’s no…”

She paused thoughtfully. And then her eyes went wide as saucers as her palm slapped her forehead. “Oh My God, I get it!!!”

I just smiled. “Go ahead, say it. There’s no what?”

“There’s no Feeling. No Connection,” she said, her eyes still wide in wonder. “No connection between perceiver and the object of perception!”

She’d got it. Well, almost all of it. All that was left for me to do was fill in the blanks and connect the dots.

“Drishti,” I said, then paused for effect. “What exactly does it mean? Your name. What does it mean, Drishti?”

“Vision,” she said, a confused look on her face. To be wiped off a moment later with a look of comprehension.

“Nope,” went I. Vision is something far deeper. The wordDrishti actually means “Sight”, to look at. It is a function of the eyes. It is something we all do. The ‘photographer’ who takes a picture without knowing why he’s taking it has Dhristi, as does a person who merely looks at the idol in the temple – or gazes at it without feeling and connection. All this is Drishti. Drishti is mere looking, Drishti is mere sight. Nothing more.”

“And Darshan?” she ventured.

“Tell me, when you’ve gazed at the idol in a temple with real feeling, have you at times experienced the idol gazing back?”

“Yes, many a times,” she said.

“And it was only when the intensity of your feeling towards the idol was… well, quite intense, isn’t it?”

“Absolutely,” she said, a bit confused about what I was pointing to.

I rested my elbows on my knees, leaning forward. “Remember what I often say with respect to photography: that if you really, really observe something for long enough, it’ll literally tell you how to go about photographing it. Have you tried – and experienced – this for yourself?”

I wish that I had a camera to photograph her eyebrows. They shot so high they almost went off her scalp.

“Oh yes I do! My God, I can’t believe the similarities,” she exclaimed.

“They’re not similar, they’re the same thing! That something that you observe which tells you how to photograph it — it really cannot tell you how to go about photographing it. Nor can the idol gaze back at you. Not literally. Not unless there is something more at work, and that more has nothing to do with mere Sight – nothing to do with Drishti. But rather, it has everything to do with you – with your feeling. That feeling – and there is nothing exclusive to religion about it – is what in India is called “Bhaav” or Emotion. It is this Bhaav that cements the connection – the link – between the object of perception and the perceiver. It is this connection – and this alone – that is responsible for the child being able to make an emotive drawing of a family outing. It is this connection – and this alone – that makes an inanimate object speak to you on how it should be photographed. It is this connection – and this alone – that makes the idol gaze back. It is this connection – and this alone – that all art, all photography, all music is all about at the end of the day!”

I paused, my response having emptied my lungs of air. She was silent, soaking in what I’d said. A few seconds passed before I continued.

“That connection,” I went on, “is all that matters. And that connection is entirely within you being the perceiver. Being within you, it is distinct from Sight (Drishti). It is – and I cannot emphasize this enough – it is beyond mere looking, beyond mere sight. It is literally In-sight! A feeling, no matter how fleeting or transitory, of the relationship – the connection – between you and your… call it whatever you wish to, they’re all the same at the end of the day: object of affection, devotion, observation, perception, what you wish to photograph… It’s the same thread running through everything. Do you understand what I’m saying, Drishti?”

She chose not to answer my question. She just smiled and went “The camera really doesn’t matter, The Connection does. That’s Darshan!”

I smiled back, knowing that the time for words was over. Drishti had had her Darshan.

(Strange as it may sound, to be continued)